Today I came upon an excellent post about "ten upcoming technologies that may change the world" by Alvaris Falcon. Great food for thought, allowing me to catch up on all these new technologies and expand upon two of them-Google Glass or augmented reality and 3D printing or rapid prototyping based upon my exposure to them this past year.

AUGMENTED REALITY (AR)

Ten years ago the technology introduced in the film "Minority Report" stood marketing experts on their ears.

|

| Tom Cruise wearing "data gloves" in front of translucent glass in the 2002 film "Minority Report" |

"...the concept of Augmented Reality conjures up that memorable scene in Steven Spielberg’s 2002 movie Minority Report in which Tom Cruise’s character strolls through a mall while being assaulted by marketing messages of a highly personal nature. A Guinness billboard addresses him by name and tells him he could use a drink; in the Gap store, a hologram of an assistant asks him if he is enjoying his previous purchase; an American Express advert shows a giant 3D credit card embossed with his membership details. It is an unsettlingly depiction of an advertising nirvana, all made possible by the supposed existence of retinal scanners."The data glove interface depicted in the photo above is a form of virtual reality (VR). VR differs from AR in that it is an entirely virtual experience and has no anchor in the physical world. AR experiences on the other hand, use computer-enhanced glass to augment or overlap reality in real-time with sensory data or other useful information as applied to the world around us. We are familiar with the AR in this montage taken from the 1984 film "The Terminator":

"In the Terminator movies, Arnold Schwarzenegger’s character sees the world with data superimposed on his visual field—virtual captions that enhance the cyborg’s scan of a scene. In stories by the science fiction author Vernor Vinge, characters rely on electronic contact lenses, rather than smartphones or brain implants, for seamless access to information that appears right before their eyes." [Augmented Reality in a Contact Lens, by B.A. Parviz 9.30.09]

|

| Bionic Contact Lens "A Twinkle in The Eye" |

"Confusingly, both AR and Virtual Reality share key elements that allow users to experience enhanced interactions through digital and online input, and often the terms are used interchangeably: with the increasing advancements of gesture-based interfaces (think the Kinect), distinctions between Virtual Reality and AR are becoming increasingly irrelevant." [The Next Web : "How augmented reality will change the way we live" 8.25.12]

"[Google] Glass is, simply put, a computer built into the frame of a pair of glasses, and it’s the device that will make augmented reality part of our daily lives. With the half-inch (1.3 cm) display, which comes into focus when you look up and to the right, users will be able to take and share photos, video-chat, check appointments and access maps and the Web. Consumers should be able to buy Google Glass by 2014.""Sight", a short sci-fi film by Eran May-raz and Daniel Lazo (publ. 8/1/12) imagines a world in which Google Glass-inspired apps are everywhere which Forbes tech writer AW Kosner says "makes Google Glass look tame".

Beyond personal eyeglass, General Motors Corp. researchers are working on a windshield that combines lasers, infrared sensors and a camera to take what's happening on the road and enhance it, so aging drivers with vision problems are able to see a little more clearly.

Another AR application for smart windshield glass under development in the UK:

Connecting this back to the entertainment industry, John C Abell wrote an interesting article about the roots of AR in sci-fiction for Wired: [Augmented Reality's Path From Science Fiction to Future Fact 4.13.12]

"There can be a very thin line between fantasy and science. Fantasy drives science. Set aside Geordi’s visor and today’s augmented reality glasses for a moment. Instead, look at some original Star Trek episodes to see handheld, long-range wireless communication devices and voice-input and omnipresent and seemingly omnipotent computing half a century before these nonexistent technologies became things we take for granted."

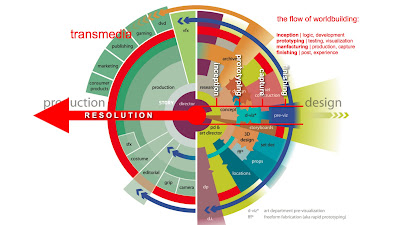

Looking forward to a relevant upcoming event, "The Science of Fiction" presented by 5D Institute in association wth USC School of Cinematic Arts (April 2013) that will expand on this concept (and others) it applies to the art of production design for film, books and games.

"Science fiction prototyping, design fiction, and world building are all established narrative devices which engage the power of Fiction to grab elusive or as yet unrevealed Science and disrupt current thinking to provoke new discoveries."3D PRINTING- RAPID PROTOTYPING

Rapid prototyping technology most familiar to me before the advent of 3D printing, used in the creation of vehicles and other props for films and theme parks, is the subtractive process known as Computer Numerical Control (CNC) milling. In the entertainment industry companies such as Trans FX (TFX) used this method for creating a number of the Batmobiles currently on tour for example.

|

| Batman vehicles on tour |

|

| Artificial jawbone created by a 3D printer |

'Skyfall' filmmakers dropped some of their $150 million-plus budget on 3D-printed scale replicas of Bond's classic Aston Martin DB5.

"Voxeljet,

a 3D printing company in Germany, created three 1:3 scale models of the

rare DB5. Each model was made from 18 separate components that were

assembled much like a real

car.

The massive VX4000 printer could have cranked out a whole car, but the

parts method created models with doors and hoods that could open and

close.

The completed models received the famous DB5 chrome paint job and bullet hole details as finishing touches during final assembly at Propshop Modelmakers in the U.K. One of the models was sacrificed to the stunt gods during filming. Another was sold by Christie's for almost $100,000. " Read this article by Amanda Kooser on CNET.

3D printing for environmental miniatures is currently being developed further by VFX pioneer Doug Trumbull known for his work on 2001: A Space Odyssey. Trumbull was in Los Angeles this year to accept the Visual Effects Society's Georges Méliès Award. I had the privilege of meeting him when he also attended and spoke at the 4th meeting of the Virtual Production Committee in February 2012.

Virtual production is essentially digital compositing of 3D elements in camera (real & virtual or virtual & virtual) in real time. Doug Trumbull has been combining elements in camera since the 70's with his Magicam System.

Trumbull is a proponent of filming optical effects and prefers using real miniatures rather than CGI for compositing. He is currently expanding on his own virtual production technique at his state-of-the-art studio in Massachusetts.

At Siggraph 2012 Conference in Los Angeles this year 3DSystems showcased CUBE the first @home 3D printer. Attendees could print their own 3D files into physical objects (ABS plastic) from working machines provided at a hands-on demo booth.

The new stop-motion feature "ParaNorman" uses full-color Zprinted puppets.

Read an in-depth article by Brian Heater with great photos: How 3D Printing Changed the Face of 'ParaNorman'

Given that we already have 3D laser scanners in use and can create accurate digital files to replicate and/or design new objects with relative ease, the applications for 3D printing truly are going to change the world.

The completed models received the famous DB5 chrome paint job and bullet hole details as finishing touches during final assembly at Propshop Modelmakers in the U.K. One of the models was sacrificed to the stunt gods during filming. Another was sold by Christie's for almost $100,000. " Read this article by Amanda Kooser on CNET.

3D printing for environmental miniatures is currently being developed further by VFX pioneer Doug Trumbull known for his work on 2001: A Space Odyssey. Trumbull was in Los Angeles this year to accept the Visual Effects Society's Georges Méliès Award. I had the privilege of meeting him when he also attended and spoke at the 4th meeting of the Virtual Production Committee in February 2012.

|

| Doug Trumbull at his studio in the Berkshire Hills of Massachusetts |

"We can make miniatures look absolutely real, that isn’t a variable. I recently looked at Blade Runner, Close Encounters and 2001 in my screening room on Blu-ray, and I could see everything that was in the original prints. Sometimes it is even better, because the grain and slight weave of physical projection is gone. All these years later the miniatures hold up and are not the slightest bit obsolete due to CGI. Miniatures are used so rarely, they are practically a lost art, though Hugo shows how successfully they can still be employed."

"Most directors aren’t comfortable in a virtual world, something I found out long ago with Magicam. Many actors, having learned their craft on a near-empty theater stage, are more comfortable. And I found that showing actors the composite on stage thrills them. “Finally, I don’t have to fake it.” If you don’t have something to show them, you wind up like 300, where everybody’s faking it because they have no solid idea about the virtual environment! My next step – something I haven’t done before except in brief experiments – is to replace the computer-generated, real-time virtual set with a miniature, which I find much more photo-realistic and believable than anything generated in a computer. Then I use Nuke and other comp techniques as needed, though I’m aiming for every shot to have at least 80 percent physical reality, rather than settling for the algorithm of the month. My tastes have always run to more organic approaches to visual effects." [ICG Magazine interview: Exposure: Douglass Trumbull 4.4.12]Trumbull discusses his role in the history in filmmaking in another great interview by Wofram Hannemann in May at FMX Conference in Stuttgart Germany [in70mm.com 5.10.12]

At Siggraph 2012 Conference in Los Angeles this year 3DSystems showcased CUBE the first @home 3D printer. Attendees could print their own 3D files into physical objects (ABS plastic) from working machines provided at a hands-on demo booth.

|

| Siggraph Attendees playing with Cube printers |

The new stop-motion feature "ParaNorman" uses full-color Zprinted puppets.

|

| ParaNorman 3d printed puppet faces |

Given that we already have 3D laser scanners in use and can create accurate digital files to replicate and/or design new objects with relative ease, the applications for 3D printing truly are going to change the world.